Tue Jan 20 2026

Hospital Discharge Is Not Patient Exit—It's Bed Recovery

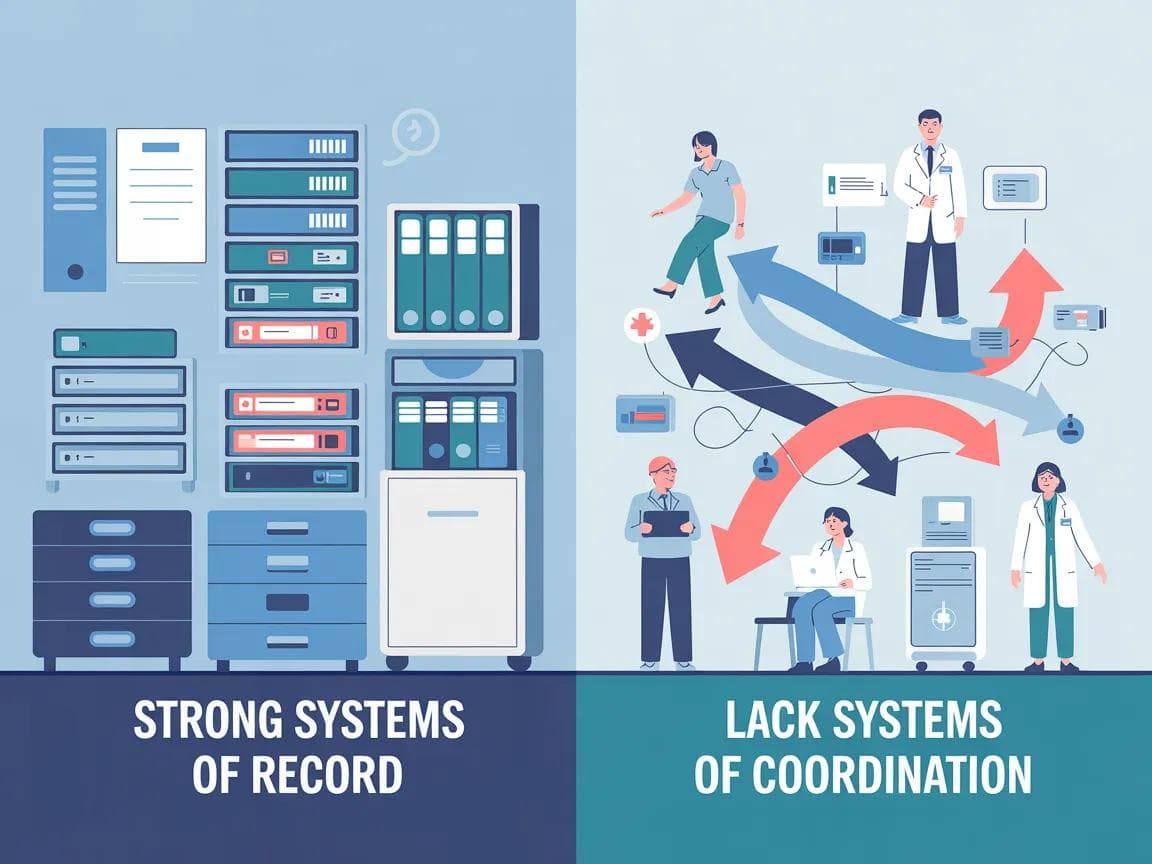

Hospitals have strong systems of record. What they largely lack are systems of coordination. Discharge isn't just a clinical event. It's an operational handoff — and in most hospitals, that handoff doesn't have a clear owner.

Discharge Is Not a Patient Leaving. It’s a Bed Returning to the System.

In hospitals, discharge is often spoken about as a single moment:

the patient leaves.

Clinically, that makes sense.

Operationally, it does not.

From an operations point of view, discharge is complete only when the bed is actually available for the next patient. And that moment usually happens after the patient has already left.

This gap — between patient exit and bed availability — is small in definition, but large in impact.

Two different meanings of “discharge”

Most hospitals implicitly operate with two definitions of discharge:

- Clinical discharge: the doctor signs off, billing is done, the patient exits.

- Operational discharge: the room is cleaned, the bed is marked ready, admissions can allocate it to the next patient.

Both are valid.

The problem is that the space between them is rarely owned or made explicit.

Discharge is treated as “done” by one part of the system while it is still very much “in progress” for another.

Hospitals have strong systems of record.

What they largely lack are systems of coordination.

When does capacity actually get released?

In practice, hospital capacity is released only when:

- housekeeping has completed room cleaning, and

- admissions (or the bed management function) has formally marked the bed as ready in the HMS.

Until that happens, the bed is effectively still blocked — even if the patient has left hours ago.

Patient exit ≠ bed availability.

Your HMS knows when a patient leaves.

It doesn’t know when a bed has truly returned to the system.

This distinction matters because hospitals don’t run out of patients.

They run out of usable beds.

Why hospitals feel full despite discharges

Many hospitals experience days where:

- multiple patients have been discharged,

- yet admissions are delayed,

- emergency waits increase,

- OT schedules slip,

- and beds still feel unavailable.

This often isn’t because discharge didn’t happen.

It’s because capacity was not returned to the system in time.

After patient exit, time is commonly lost in:

- housekeeping completion not being visible downstream,

- admissions not being proactively informed,

- beds not being marked ready in real time.

Nothing is “wrong” in isolation.

The gap exists between teams.

The ownership problem

A critical question arises here:

Who owns the gap between patient leaving and bed becoming available?

In many hospitals, the honest answer is: no one explicitly.

- Nursing ensures the patient leaves.

- Housekeeping cleans the room.

- Admissions waits for confirmation.

- Operations finds out only when a bed is still unavailable.

Each function does its job.

But the handoff between them is often assumed, not owned.

Discharge isn’t just a clinical event.

It’s an operational handoff — and in most hospitals, that handoff doesn’t have a clear owner.

This is why follow-ups, chasing, and escalation become routine — not because people are careless, but because responsibility for the sequence is unclear.

Is bed availability a medical or operational concept?

Hospitals often treat bed availability as a clinical outcome.

In reality, it behaves like an operational constraint.

Beds don’t become available when care ends.

They become available when coordination completes.

That distinction explains why:

- accreditation alone doesn’t eliminate delays,

- systems of record don’t reflect real-time readiness,

- and faster work inside departments doesn’t always reduce waiting outside them.

Why this gap has existed for decades

This is not a new problem.

Hospitals have lived with this gap for years because:

- it sits between departments,

- it spans shifts and floors,

- and it doesn’t belong cleanly to any single function.

As a result, informal workarounds emerge:

- calls,

- messages,

- personal follow-ups,

- “please check once” requests.

These work — until scale, volume, or shift changes break them.

Variability across hospitals (and why the pattern still holds)

It’s important to acknowledge that discharge operations are not identical across hospitals.

Workflows vary by size, specialty, staffing models, and systems in place.

Some hospitals manage housekeeping coordination and bed marking better than others.

But across settings, the same pattern often appears:

the moment a patient leaves is not the same moment capacity is actually released, and the ownership of that gap is rarely explicit.

That ambiguity — not lack of effort — is what creates delay.

Why naming this gap matters

If discharge is defined only as patient exit:

- beds stay blocked longer than necessary,

- admissions remain reactive,

- housekeeping becomes a bottleneck by default,

- and nurses absorb the coordination load.

When discharge is understood as capacity recovery, the conversation changes.

Not toward faster work —

but toward clearer handoffs, visibility, and ownership.

Closing thought

Hospitals don’t struggle with discharge because people aren’t working hard.

They struggle because the system treats discharge as an endpoint, when operationally it is a transition.

Until the gap between patient exit and bed readiness is made visible and owned, hospitals will continue to feel full — even when patients are leaving.

Written by

Prasanna k Ram

Founder & CEO

View LinkedIn Profile